Sept: the helicopter, 4 planes, taxis by the dozen; a writing retreat, a terrible phone call and a dash to Spain... Oh, please, Earth, I beg you, let me be still.

There is something above me, around me, something between me and the sky... the air is thick with a trillion dancing particles, heavy on my skin, filling my eyes...

James Edwards -My son, my hero, my Guardian Angel, Artist/T-shirt designer - Cool Dude on A Skateboard! He wore it with pride. We now plan to build a website, selling prints of his works for Brain Tumour Research

September - WHAT ON EARTH has it been like? The emporium, the full circle of all that life is, has come my way: going through the weeks; hard work, the expected— then shock, despair, grief, wonder and awe; a cacophony of emotions, sobbing and laughter all in one half of an hour. Since moving here, my mum’s mum died, age 97, I’d only been here a few weeks. Then, in early September, Simon’s father had a stroke and is now enduring the agonising process of rehabilitation - finding his words and putting them in order. My mother-in-law, Norma, summoning great strength again. And now Uncle Peter… I have only ever known life with Uncle Peter very firmly in it… Life and death are one, side by side, entwined, and I am on island, off island, on, off again.

Why can’t our clever brains fathom the simple truth - that someone is gone and we won’t see them again? We can’t and don’t want to believe it. We think we are going to have time to say goodbye to aging loved ones, those people who have watched you grow, like my Uncle Peter, always there, a hefty unit, SO SOLID, no idea of his strength; a cuddle from him could take your breath away. He was a listener, always watching, always pleased to see me. You think you’ll know when it’s nearly their time; so you will make time to cherish them. But in truth, between being here — and not here — there is no time at all. And even if you can predict a passing - you tell yourself it’s coming - still, you cannot comprehend it.

It’s also ok to be in denial. It’s how we get through. So, when someone dies, it’s sudden, the shock is profound, it lingers, you’re trembling inside, all is surreal. As we cried together, I said to Auntie Carolyn, ‘It’s as though he’s vanished…’ — ‘He has,’ she replied. I want to wrap her up and protect her from the need to be strong. Yes, she will have to find strength and she will; Yes, we know he had a good life. Yes - sixty years of memories and he was 82. All of that. But those truths are not helpful. Right now, grief needs to scream and shout - I’ve lost my husband and it hurts like hell.

Pentle Bay, the back of the beach, thick sea mist - what is it about the back of the beach? My eyes are drawn here… I can feel the fullness of high tide, but I cannot see it.

Welcome to my 16th Newsletter on Love and Loss. Subscription is free. I’m reminding myself that I don’t have to live the whole of life at once. And this is what I keep saying to my Aunt - You only have to get through the next hour. But how can a woman in her 80’s, her lover by her side for SIXTY YEARS, how can she process this? She asks, over and over, ‘What am I going to do without him?’

‘You’ll just get through days,’ I say, ‘somehow, time takes you on.’ I don’t know what else to say and so I give her a foot rub. ‘Try to give your mind a rest, and just feel your feet.’ I know in time, she’ll begin to feel his presence again.

Many weeks have passed since my last post. The leaves are drying and curling. The ground is soft with detritus, organic matter, dying and giving itself back. I am pruning until my hands are screaming. First week of September: Simon is away. It’s a Sunday, sunless, there is something in the air, sticky; an invisible treacle holding up the sky, heavy on my head.. today will be a struggle, between weathers, neither summer nor autumn, blue nor grey, but a white sky, shut tight, outlines are blurred, no crisp definition. Sundays are strange days. Where do I fit? I try to structure my day; the dog, the changing light and its shadows. Ernie and I - we walk, sleep, eat, walk, sleep. Simon has had to fly home in an emergency to be with his family. His father is recovering from a stroke; he’s going to be okay, but recovery is long and hard work. When bad news comes, we feel so far away. I watched him weep, 8pm, on the phone to his mum, ‘I’m coming, I’m on the next flight.’ It’s a long and winding 50 miles - electric bus, a boat, a plane, a train and a taxi.

I’ve called this picture Boat Too Big. It looks photoshopped. These cruise ships come several times a week in August. Hundreds of people disembark, often 500 at a time, for a tour of the Abbey Garden.

So, for a week, it’s just me and Ernie, together on this quiet island, 1.15 square miles - changing gear, sinking back down, resting into itself. Suitcases are loaded onto helicopters and boats and tiny planes. Sun lounge cushions put away. Autumn peace-seekers are arriving. A different type of tourist now, September people; they want less, say less, expect less from the sun, they walk slowly, sit quietly. They bring binoculars, wide lenses -searching for birds and late flowering beauties, like the Nerines that have replaced the Agapanthus. Young couples come to push prams, up early - I see sleeping feet sticking out, I spy dummies, the rapid sucking slows as dreams go by. In the cottage across the road there was a little boy here for 2 or 3 weeks. About James’ age, 5 or 6, blue glasses just like his. I kept bumping into him. Gasped and shifted my gaze. He’s gone and I can breathe again. Autumn brings relief - these next months will allow proper gardening, AT LAST! As the season changes I have an ache for home, a night at the cinema, a bath, a log fire. The winter will really test us. I will cycle home in the dark. Walk Ernie in pitch black - head torch on. On wet days we come in and fill our tiny space with dripping coats, sodden boots. There is no room to move. Ernie is stressed and begs to go out.

I work alone more now. The boys cut hedges and strim. I am pulling out the old and dead and planting new. The team meets 8am to discuss what needs doing, the arrivals. We decide who’s going to cut flowers and foliage for the flower bunches - red hot pokers, Nerines, Pittosporum, Eucalyptus, reeds from the lake, anything green with a stem that won’t wilt. Waiting for the flowers I water pots and weed in the communal areas; we can’t go into cottages until 9.30am and cannot use machinery until then either. We find quiet things to do, easing into the day, snipping Hebes, Marguerites with sheers, organising tools, filling tractors with fuel. I find an empty house and lose myself in its borders.

Goodbye Agapanthus - Hello Nerines…

Picking flowers for the cottages - Nerines bowdenii, autumn flowering bulb

Simon still away, visiting the hospital everyday. His dad will come home soon. He’s walking and saying a few words. Norma is strong. She says, we’ve been through the worst, we can cope. Sunday alone, I knew there was a band on, 2-4pm at the pub. I decided to go for a roast with Ernie. The beer garden was packed. The sun was in the air but nowhere to be seen - warmth floating through layers. It was muggy. It took forever to get my beer. The twins were there, Sam and Alex, the lovely girls who work at the cafe. They love to make a fuss of Ernie. They are gentle, kind, almost identical with sweet, kitten-like faces. There is a calmness to them, is that a thing with twins? As if the noise of being human is shared and softened, divided in two, a soul shared; they are two but one, always together somehow. Standing between them, I am in the middle of something, a shared energy. Spending their summer together, they are complete. Perhaps their composure is born from a feeling that they will never be lonely because, in the womb, not alone, used to sharing a small space, they are at ease. I surprise myself here; did not expect to write about the twins. In truth, I hardly know them. My perceptions run away with my overthinking. Can you trust someone with a wild imagination? Substack helps me to grow my confidence, quiet the critic on my shoulder. This opinionated world brings a crisis of confidence. We feel judged, we judge ourselves. We are deaf to our own truths because we are listening out for what others think. But look at Ernie - he lies down on the warm concrete in the beer garden, on his back, legs akimbo, bearing all, not a care, then, onto his side, he’s leaning into Sam’s ankles. She likes it. ‘It’s just lovely having a dog around,’ she says. We chat and the music starts. My tummy is full of beer and I lose my appetite. Too many people, too much noise. Roast £25… Ernie and I walk home. Egg on toast and a nap.

Tuesday, 5 am, Simon still away. Last night I ate another ‘Simon is away’ meal - these meals that I knock together alone, when eating is not an event, they are strange. No roast potatoes or chips for days. No sauces, no faff. These meals nourish me and use things up. Lentils. Broth. Noodles. Spinach floating in salty goodness. Meals made from the cupboard. After a bowl of dahl I got restless. The beach was not there, but the strangest non-light, a thick sea mist so low I was walking inside of a cloud. I was about to go to bed when I looked out and thought, I must get closer to the high tide. The world had shrunk, the island seemed inside a dream, a bubble, a snow globe shaker. St Martins, the opposite island, had completely vanished. There was just me, a few feral kids. Half of Old Grimsby Quay visible, the cobbled path leading into nowhere. The sea was silent, like when you are standing at the side of a lake. It was late, maybe 8.30. In the twilight, the young children, maybe 4 or 5, were playing on the shoreline. I craved for the water to take me out of my head. I slipped off my sandals and pulled my cords up over my knees. The water is ice that burns and numbs and makes your skin buzz with aliveness.

James took this photo on 24th Feb 2019 at 18.27. He was four years old. We look younger here!

Simon returns with a terrible chest infection he caught at the hospital visiting his Dad. He feels so bad, leaving them, and now will feel guilty being here. He has a week’s sick note and antibiotics. He is really poorly. Breathless and weak. Returning to the hospital has brought back horrid scenes for him. Re-traumatised, so low. The coughing is keeping us both awake. We are craving a proper holiday, real heat. The summer weather has left us feeling cheated. This longing for something is constant; we wade through long days, lessons of infinite curves. I am the student and time is the teacher, pulling me on, giving me lines and lists, numbers and ticking off. Can’t go back, only towards. But here, there, notice the stillness. Accept that, IN LIFE WE LOSE, and we ask, in the dark hours, how will I go on? And because we don’t know the answer we panic. And that’s it! Therein lies the problem - we go wrong, bullying ourselves; we must go on, and on, taking life in too big a dose. But, for a moment, an hour or two, you don’t have to go on. You can just be here.

So please, Earth I beg you, let me be still. I’ll take a blanket and walk until I sense the elements, feel the rhythm of the sea in my heart. Content, away from cottages, cleaners and tractors - here, where land meets sea - I am the line on the shore where things that float and drift are left by the hightide. I look at the miscellany of what’s been tossed and dumped by the last lapping - I see myself - part of the debris, sodden and salted by the under currents. What it all amounts to is something and nothing. Things don’t need meaning. Ribbons of kelp with no roots, no bed to grow from; they lie, crisping up, feeding flies. The top half of a scallop shell, rocks rolled on the rough bed, smoothed into pebbles. And there’s plastic too, of course, not a lot but the odd bottle top, shards of a cup, a faded bag? Not sure anymore, it’s broken down, mingling, fitting right in, plastic off-cuts, lost and loose. The beach has an energy like no other. Things come here to find space, things pushed to one side, it’s where we come to search the horizon. Things sit a while or go right back out with the tide. Some reach the back of the beach and might not ever leave… What is it about the back of the beach? Small mountains of sand untouched, unsoaked, the border between worlds, hiding the road, shushing the wind in the trees, these soft slopes are shapes in the land, evolving, at the mercy of all the winds - and in the face of it all, they sit here, still and quiet. This is the place.

View from the helicopter - returning to Tresco, after a week away writing.

Last week of September: I’d been craving solitude like never before. A selfish holiday. I know someone who knows someone - kind people who can’t know just what they did for me - offering a free cottage on a quiet creek somewhere between Truro and St Mawes. (I escaped here to the isles, and now I am escaping to the mainland. All this ocean makes me feel small. I needed more land for a while.) It was one of the best things I have ever done. I worked on my book for five days. I sat outside, watching the silent green water seep inland. I had no car, no pub, no shop. I was stranded. I made strange meals out of the few items I took: tea, one bottle of red wine, spaghetti, tinned toms, stock cubes, anchovies, broccoli, a grapefruit, six eggs, bread, cheese, oats, milk, butter, honey. The best meals are always the most basic. I’d forgotten olive oil -was eating pasta and fried eggs with butter. We make meals like this a lot now, because popping to the shop is a bike ride up a steep hill. And now closed on Sundays - we make do. So I was practiced at this for my days stranded on the creek. I wrote and slept and lay in a giant bath tub. I lit a fire and listened to the flames, the radio. Walking inland, beside the creek, I found The Secret Cupboard Tea Garden. I sat amongst apple trees watching the water, alone but with company - perched on a dead branch, a single magpie, the first I’ve seen since living in the isles. It watched me eat my ploughman’s lunch - that would have cost me fifty quid on Tresco. I took half of it away and made a giant cheese scone, chunk of cheese, thick ham and pork pie, last two more days.

Back to my new normal - or so I thought: Two days after I returned, at work Monday morning, I’d just finished 18 bunches of flowers for the arrivals, it was ten am, time for my porridge—

My phone rings. And that was it - life was upside down again. My mother is shrieking down the phone - Peter's died in Spain.

And there it comes, the familiar jerk in the gut. The wind sucked from the throat. One of the drivers took me home. I went in, poured a Jameson’s and booked a flight. I took a deep breath and made a video call to my cousin. He saw my face, and he put his hand over his eyes and wept. ‘I love you,’ I said. Another big breath, a video call to Auntie Carolyn, with her friends all around her, a blanket on her shoulders. All she could muster was, ‘I can’t wait to see you.’

‘We’re coming, I said, ‘We’re coming.’ Two and half hours from Malaga, my aunt and uncle have a made a wonderful retreat from their busy lives as caravan park proprietors, a few miles from Padstow. Now retired, but never really retired, they spend a few weeks out of season in Casa Pedro, softening aging bones with proper warmth. Peter’s Spanish Garden is breathtaking. Next I called my Dad, I was crying. He hadn’t heard. ‘I’ve got to sit down,’ he said and hung up on me.

Flowers I cut with much trepidation, from Casa Pedro, for his casket, with every snip feeling Peter’s eyes upon me, I could feel him saying, ‘What the hell er you doin, Maid, cuttin my flowers?’

Casa Pedro, front garden. Sadly, now up for sale.

Rest in Peace, dear Uncle Peter. We promise we will all look your beloved, Carolyn.

24 hours and two plane rides later, I was walking off a Jet2 flight in Malaga, under an enormous blue sky, 28 degrees, a small bag - summer and funeral clothes. In that time I’d got a 3 pm boat from Tresco to St Mary’s, a 4.30 flight to Penzance. A friend picked me up and dropped me in a layby an hour down the road, where I joined two taxis - my cousin, cousin’s wife, their two children, my mother, brother, sister-in-law, and Peter’s sister, Christine. Nearly three hours later 9 of us checked into the Bristol Hilton, drinks and tears in the bar, terrible pizza. We slept for 3 or 4 hours before checking in at the airport at 4.30 am. All of us just wanted to be with Carolyn. Every minute of imagining her without her family was heart wrenching. After three hours in a taxi from the airport, finally we were with her, holding her, crying with her. This is how life throws you about. But what a profoundly beautiful thing - we are so lucky to have family. Since losing James, we’ve drifted a bit. A bomb landed in our lives, sent us all sideways, blown to bits, far and wide; gatherings lessened, texts replaced talking, bonds seemed broken, lines disconnected. We just all love each other so much; it was too painful to be together. It has taken another tragedy to bring us closer again. We couldn’t believe it. It couldn’t be possible. Peter was fine, having a lovely holiday, had lunch with a dozen friends on Sunday???? On Monday morning he was in his garden, under a Spanish sun, pottering as he did, draining the pool, preparing to leave two days later. Carolyn went into the garden, to tell him his breakfast was ready, ‘Peter, come on, wake up—’

When we arrived, one by one we hugged her and wept. Their bungalow is down a dusty road, a rural area, 15 miles from Cadiz. They’d made it beautiful. But now, instantly, its whole atmosphere had changed - strange and uncertain, something from a story, the past, the good life, 20 years of escaping to the sun. I went to sit on Peter’s side of the bed, to cry. I looked at his slippers. Back outside, there was already a celebrant there, writing notes for the eulogy. I got drinks for people. Found some Gaviscon in the cupboard. (For weeks now I’ve had the horrible sensation of acid stuck in my throat.)

He’d been gone 24 hours. He was being cremated in the morning. Mark turned detective, desperate to make sense, retracing his dad’s last steps - ‘He took his statin Sunday night,’ he said. There’s his watch, his wallet… We sat amongst Peter’s plants, drinking his drink - gin and tonic. I’d not been out here to see them for years. I should have brought James? Why didn’t I? I should have appreciated Peter more? Guilt and regret poured in… I hugged my brother as he sat on the sun lounger, crying, staring at Peter’s half drained pool.

Carolyn was desperate to leave the villa. We took her to a hotel, a sprawling complex on the La Barossa beach. 400 rooms and a map to find ours. All ten of us checked in, and we went to lie under parasols by the pool. Cold beer. Crisps. We didn’t fit in. Everyone else, on holiday. We were suddenly starving. Mark’s head was spinning. So much to organise, what to do with the house. I thought how that would have been my James one day, enduring parent loss without a sibling to share it. I can’t imagine how he feels. I have both my parents still. Mark has always been another brother to us. I hope he doesn’t feel alone. But I guess it’s not the same. Having my cousin’s children with us, Noa and Siena, 10 and 13, brought wonderful light relief. Talking to them was a good distraction. The following day, at noon, as the midday sun poured heat into the white walls surrounding us, we sat together, holding hands, an audience trembling, in a Spanish crematorium, listening to the story of Peter’s life.

This is how they do it in Spain. Quick. No time to think - so alien to us. He’d died on the Monday. We hardly know the truth, and yet here we are, on Wednesday, laying flowers on his casket. Afterwards we went Sergio’s, Peter’s favourite bar. Rustic does not really do it justice. It’s a roadside stop for men in overalls. Anchovies, cold beer, cafe con leche… A place with a heart so big, you want to sit and just watch human life. When we arrived, Sergio burst into tears. He’d got so used to Pedro, sitting at the bar, watching, somehow communicating with gestures and smiles. On Thursday we lay by the pool enduring a speaker blaring disco music, watching the Germans do an aqua fit class. Friday - a blur. And on Saturday morning back to the airport, cousin Mark carrying his Dad in an urn. I took a picture of him and his Mum, shell-shocked, sitting in the airport, with his Dad’s ashes on the third chair. They look like they’ve been hit by a train.

Let me tell you about Uncle Peter, genuine Cornishman. Two expressions: Salt of the Earth, and Larger than Life. He liked to watch the world and say little. He had a wisdom, he knew a simple life was best; believed that eating should be at home, not in restaurants. He liked to eat a tomato and take the seed from its centre and grow it again. He made a greenhouse from old windows, filled Higher Harlyn Park with flowers, all grown from seed he’d collected. He did not waste money. His life was a beautiful routine. Up early, overalls on, tinker, potter, plant and grow, make and mend, make-do. He wasn’t trying to get somewhere. His needs were little. He went to the pub every afternoon for an hour or two. It was not about the drink - always the culture, the heart of the village, to sit with friends. At two pm, returning home, lunch was waiting. I might be wrong, but to my eyes it seemed, he really knew how to relax. Properly relax. His stillness made me feel - I talk too much. Think too much.

So, we are here, breathing, beneath the birdsong, the sky— and then, we are gone, to float and drift and fly amongst all that we cannot see. Not here, but still here. I spent two nights with Auntie Carolyn. I wanted to be there when she woke in the night, looking for her husband.

Coming back here was hard. Leaving my family, another member missing. I am back in the middle of the sea. I love my family more than ever. Twice a day I am filled up with the incoming tide. What is it about high tide? What is it about the back of the beach? Where does the sky begin? We are inside it, but tricked into the belief that we are looking at something far away: The Universe, all the way up there! But in truth of course we are its elements, right here, in it, one tiny sum of it. (That’s how I know James is with me.) Look — really look, there is the bay, full to the brim, the world out there, has come in! From where? We can only imagine, each drop’s been twice around the world while you worked, slept and ate, filling all the coves and crannies, always moving, guided by the moon. And now, choosing the perfect spot to lay down my blanket, here is the back of the beach, where the light falls on golden strands. Unscrew the flask. Pour the hot tea. A single digestive, half for me, half for Ernie. It’s quieter here, than down by the shore where the sea speaks, where two worlds meet on broken shells and shrinking stone. No splash, no ice cold slap or screaming shins. My steady breath is an invisible rope pulling James in. Ernie sniffs the air - he knows the secrets, I’m certain of that. I’m trying to stop time, stop the racing, waiting for something, a sign from another dimension I can’t see, something written in the clouds. I can feel a million messages, suspended, fizzing, neither here nor there, never landing. And all I can do is imagine, I CANNOT KNOW the secrets. I must make peace with that. And that’s when it hits me, I’m not making it up - James is here. If I believe it, then it’s real. Who can disagree?

Who are when alone? Solitude can wake up forgotten sides of ourselves. These times put up your boundaries and feel the beating heart of your soul. Hidden needs can emerge, the strangeness seems uncomfortable but you later learn the benefits. We forget things we’re good at, things we love, a new energy awakens. Relationships can swallow you, especially when living in such a small space. We get irritable, often forget all we need is an hour to ourselves.

The dull silver light, the water so still it felt thick, like liquid metal. Looking down, crystal clear water, my feet submerged looked swollen, jelly like, on the seabed. For a moment, I could not move, as though afraid I might fall out of the picture, as if the surrounding fog, the unseen nothingness, was a passage to another world - and if I moved, I might disappear.

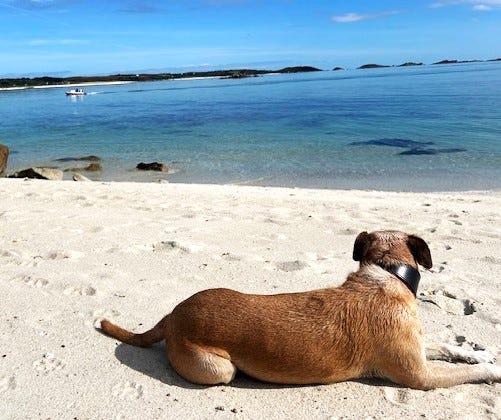

Ernie loves to disappear, to the back of the beach. On muggy days I try to get him in the sea, he paddles, but after a few minutes he can’t resist the pull - something is calling him from the back of the beach and he must sprint from the shore to wander amongst the dunes. Prowling for rabbits.

I planned to write all about the new people in my life, the new plants, but another time, because life happens, life takes us. I must let it happen.

Waking the dog at 6.30am.

Thank you for your support and your time taken to read my words. You help me to feel part of something. You encourage me to write. This is how I heal, how I keep going.